Superiority or Inferiority Complexes? Collective Self-Perceptions and Global Business

- Adam Raelson

- Nov 16, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Nov 17, 2025

A note before we begin:

This article does not argue that any culture is superior or inferior to another, nor that people from one country always behave a certain way. Instead, it explores how cultures tend to perceive themselves, shaped by history, economics, and geopolitical narratives, and how those collective, internal stories may subconsciously influence behavior in multinational business environments. These are patterns, not prescriptions, and individuals vary widely.

Why Cultural Self-Perception Matters

Every culture develops its own narrative about its place in the world. Some countries carry a strong sense of global influence. Others hold legacies of being overlooked, dominated, or underestimated.

Over time, these collective experiences shape how people:

Express confidence

Navigate cross-border hierarchies

Handle visibility

Challenge ideas

Negotiate across borders

Collaborate in mixed-culture teams

When these psychological undercurrents go unseen, they can quietly distort trust or decision-making across global organizations.

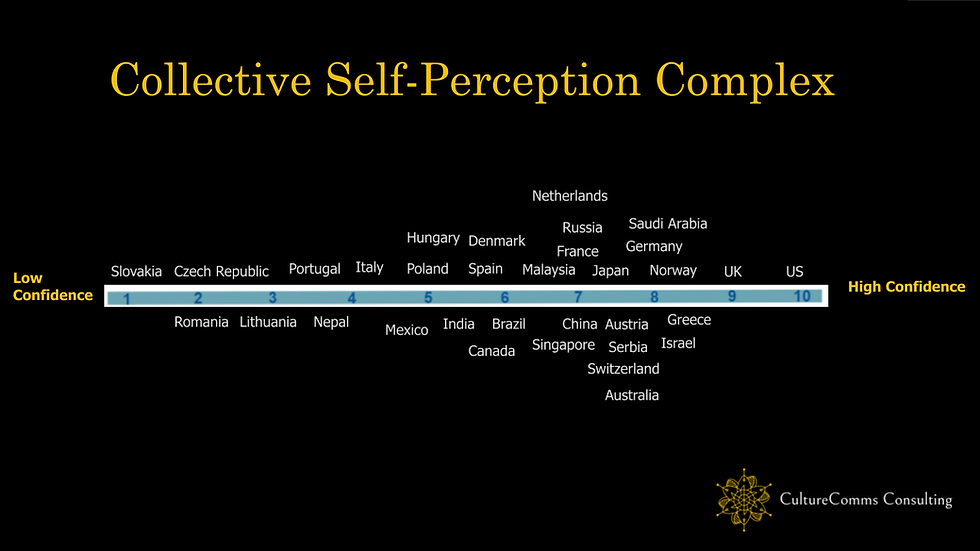

The Spectrum of Cultural Self-Perception

Cultures tend to fall somewhere on a broad continuum of collective self-confidence. Some project a strong global presence. Others adopt a more cautious or deferential posture. Most are somewhere in the middle.

This is not about worth. It is about how cultures see themselves relative to the rest of the world.

So how does this manifest in global business? Read on:

1. Cultures with Lower Collective Self-Confidence

Often found in regions historically shaped by occupation, overshadowed by larger neighbors, or frequently underestimated on the global stage.

In global business, this often appears as:

Strong expertise but reluctance to self-promote

Hesitation to challenge headquarters abroad or dominant cultures

Preference for caution and local acknowledgment

Skepticism of foreign management (especially if headquarters is abroad)

Need for trust before speaking openly

The risk? Their competence can be overlooked unless space is actively created for them to contribute.

Example countries: Slovakia, Czech Republic, Romania, Bulgaria, Portugal, Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), Nepal

2. Cultures in the Mid-Range of Collective Self-Confidence

These cultures show confidence in some contexts but defer in others. Pride and sensitivity can coexist.

In business, this can look like:

Comfort leading locally, but less so globally

Adaptability to different styles, but sometimes at the expense of clarity

Assertiveness that fluctuates depending on who is in the room

Sensitivity to perceived status differences

The risk? Their behaviors may be misread as inconsistency or unpredictability, when in reality they are navigating complex relational dynamics from a holistic point-of-view.

Example countries: Italy, Spain, South Africa, India, Finland, Mexico, Brazil, South Korea, Sweden, Denmark, Turkey

3. Cultures with Higher Collective Self-Confidence

Often countries with global economic influence, strong national identity, or histories of leadership or dominance.

In global business, this may appear as:

Strong points-of-view

Comfort with visibility, challenge, and debate

Willingness to lead discussions and assuming the role to define direction

May occasionally disregard concerns from other regional offices

Expectation that others will match their style

The risk? They may unintentionally overshadow or silence other countries, or butt heads with other high confidence cultures.

Example countries: China, Russia, France, Austria, Japan, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Germany, Norway, Greece, United Kingdom, United States

The Dynamic Most Organizations Overlook

When a high-self-confidence culture collaborates with a low-self-confidence culture, something predictable happens:

One side speaks first. The other waits.

One side frames the agenda. The other adapts.

One asserts. The other accommodates.

No one intends to create hierarchy, but history and collective psychology quietly do it for them.

So How Can Global Companies Balance This?

Rotate speaking order intentionally.

Coach all cultures to communicate with clarity.

Train higher-confidence cultures to invite perspectives.

Acknowledge historical legacies may be underlying dynamics affecting collaboration.

Don’t mistake modesty for lack of competence.

Ensure global decision-making isn’t dominated by a handful of high-confidence cultures.

Remember, every culture carries a story. Some stories are shaped by centuries of global influence or empires. Others by centuries of being overshadowed or underestimated. (Most by both).

Understanding these stories is not about labelling nations or keeping nations in their historical places. It’s about seeing the forces that may quietly shape global collaboration. When organizations learn to recognize and balance these dynamics, something powerful happens: people feel heard, teams become more equal ,and global strategy becomes genuinely global.

Every market has its own story. We'll help you turn the pages.

Comments