Greenland, Culture, and Geopolitics: High-Stakes Negotiation for Leaders in an Uneasy World

- Adam Raelson

- Jan 16

- 4 min read

Greenland has probably been on everyone’s minds more now than at any time since 982 A.D., when Erik the Red landed on its shores and carried the news back to his Viking society! The world’s attention has recently turned to include Greenland, triggered by the U.S. government under the Trump administration’s repeated expressions of interest in obtaining the island for security reasons.

Although we are seeing live geopolitical drama, the deeper story is a live case study for leaders navigating complex multinational negotiations. Greenland may be small in population (approx. 57,000 people), but its story reveals the interplay of local culture, foreign management, and hierarchy perception, which drives outcomes in any high-stakes international context.

Greenland: Local Voice, Contextual Awareness

Greenland’s population is primarily Inuit, with cultural roots shaped by centuries of life in extreme Arctic environments where community interdependence and deep ecological knowledge are vital. Here, the average temperature is below freezing for up to 9 months a year.

Greenland has been part of the Kingdom of Denmark since 1721, moving from colonial rule to home rule in 1979 and expanded self-government in 2009. These changes have significantly increased Greenlandic authority over internal affairs and resources, though Denmark retains control over its foreign affairs and defense. Greenlanders are now accustomed to balancing their internal priorities with the geopolitical interests of external partners.

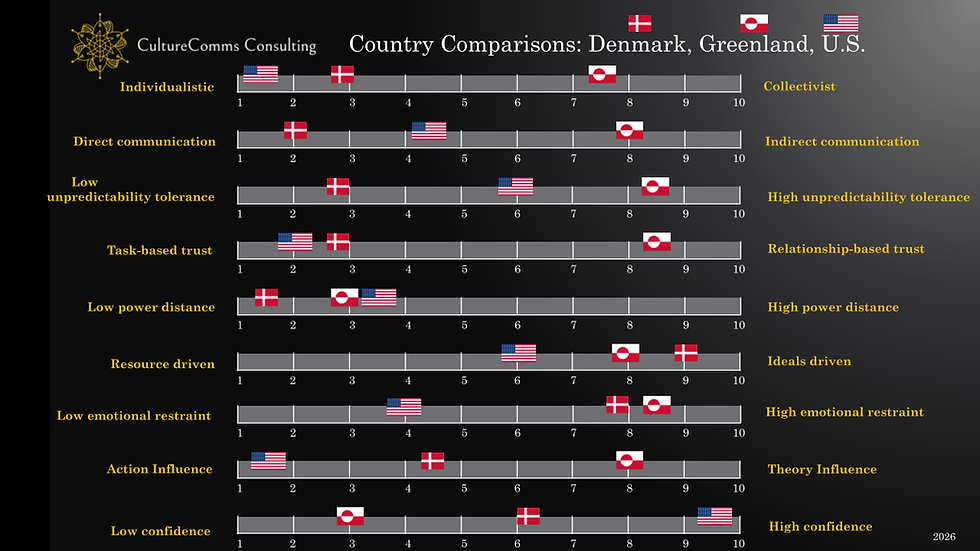

Both Danish and Greenlandic cultures value lower power distance, emphasizing accessible leadership, however, many Greenlanders’ experiences have been shaped by asymmetries, which have made externally driven processes feel imposed rather than relationship-oriented or collaborative.

Even though Greenland has a small population, their involvement in Arctic events is growing more important and dismissing it can lead to unintended consequences, eroded trust, and strained relationships. We are starting to see that Greenlandic leaders and communities are increasingly assertive about their priorities.

In any high-stakes negotiations, underestimating the depth of local perspectives and commitments can lead to challenges and instability later.

Denmark: Consensus and Legitimacy in Action

Denmark’s leadership culture is shaped by low power distance, strong consensus orientation, and respect for established processes. Decision-making and compliance tends to emphasize legitimacy, dialogue, and stability over speed or directive actions. Danes are used to very subtle expressions of authority, and influence is built through credibility and shared understanding rather than hierarchy. (Check out our other article on what leaders can learn from the Scandinavian concept of Janteloven).

With Denmark’s contemporary relationship with Greenland, this cultural style can act as both a stabilizer and a source of tension. On one hand, Denmark’s low-power-distance instincts naturally support dialogue, openness for negotiated home-run autonomy, and a reluctance to impose overt control. On the other hand, Danish culture is still very task-oriented and the historical imbalances and political realities mean that consensus processes do not always feel equitable or genuine from the Greenlandic perspective. Greenlandic indirect communication styles may feel unheard because understanding was assumed rather than explicit, and the country’s constant economic framing can feel disconnected from local cultural meaning.

For corporate leaders, Denmark’s approach to Greenland still offers a valuable lesson: sustainable outcomes are more likely when stakeholder legitimacy and long-term relationships are treated as strategic assets. Cultures like Greenland and Denmark, which emphasize egalitarian input and understatement can foster solid cooperation over time, but only when participation is not perceived purely as procedural.

The U.S.: Hierarchy, Speed, and Leverage

The United States, on the other hand, brings a more hierarchical, transactional approach to negotiations. While U.S. culture emphasizes a personally opinionated, feedback culture, ultimate decision-making is top-down, and speed often takes precedence over consensus. Unilateral moves that drive progress are a value, not a flaw. Trump-era negotiations exemplify this approach: brash, fast-moving, and leverage-focused.

This is not about viewing Denmark or Greenland as “inferior”, as U.S. American culture often fiercely strives for the ideals of basic equality and all three countries remain close allies. However, it’s about the practical application of hierarchy and power in negotiation. The U.S. is a highly self-confident culture unafraid of being outspoken. This, coupled with final top-down decision-making, means the stronger party often expects compliance or alignment, and may discount processes that slow down action. (Check out our video on U.S. cultural dimensions that align with Trump and article on cultural superiority & inferiority complexes).

Leaders from lower-power-distance cultures may interpret this as abrupt or heavy-handed, leading to friction if unanticipated. U.S. American culture is highly task-oriented versus relationship-oriented and places a lot of emphasis on speed. This is a culture that has built 24-hour services, fast food, short shopping queues, and strives for convenience. Slow-paced processes are naturally frustrating to U.S. Americans, whereby European cultures generally are used to a way of life that would trade time expense for wider input and respect for the established status-quo.

Negotiation Dynamics

The cultural contrasts in these cultures end up being relational versus transactional, long-term versus short-term, and co-creation versus top-down.

This clash illustrates a universal principle that successful and smooth negotiation outcomes are shaped not just by power, but by culture. Misreading any of these cultural dimensions risks backlash, reputational damage, or stalled agreements. There’s no debate that Greenland has become a strategic country in today’s Arctic geopolitics, but recognizing the different cultural approaches is crucial for leaders operating in high-stakes contexts, whether international or corporate.

Corporations as Mini-Worlds

The Greenland example is not only about geopolitics. It serves as an analogy for corporations navigating complexity. Departments, teams, or business units are like mini-nations:

They have unique priorities and worldviews.

They have their own local managers and ways of working.

Hierarchical decisions by leadership can create friction if cultural expectations are misread.

Small teams, like small nations, can suddenly find their voice and influence others if they feel existential threats. Don’t overlook them.

Leaders also must anticipate reactions, build trust in various ways, and execute strategies effectively.

When contrasting priorities collide, anticipate misunderstandings and mitigation strategies in place.

Conclusion

Leaders navigating high-stakes negotiations must account for culture. Ignoring these elements can be costly; integrating them provides clarity, influence, security, and resilience.

At CultureComms, we help leaders translate these insights into practical strategies. By understanding the cultural and strategic dimensions of your stakeholders, we’ll help leaders navigate complex, multinational environments with confidence, turning potential friction into opportunity.

If you want to apply the learnings of geopolitics and cultural dimensions to drive success in your organization, contact us.

Comments